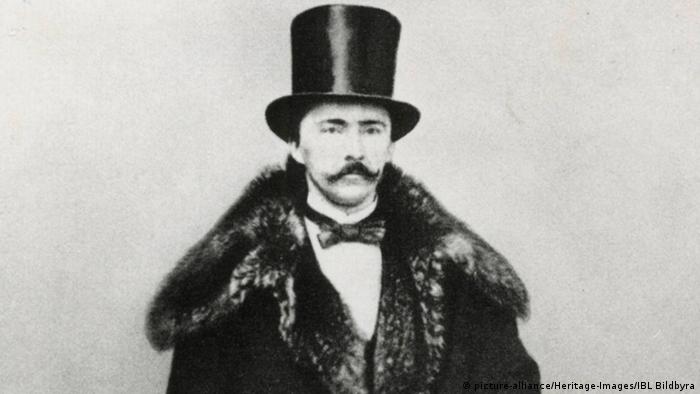

Heinrich Schliemann established archeology as the science that we know today. The German adventurer and multi-millionaire, who died 125 years ago, discovered Troy and what he thought was the Treasure of Priam.

Millionaire with a love of antiquity: Heinrich Schliemann, born in 1822 near the German city of Rostock, did not have a lucky start in life. Due to financial hardship, he broke off his studies as a young man and began a business apprenticeship. He quickly made a career using his skill and talent for languages. He built his fortune in Moscow, selling ammunition to the tsar's army. Then he began to educate himself and travel.

Heinrich Schliemann was a complex character, part dreamer and part genius in disguise. Many of his contemporaries regarded him as a utopian, as he traveled around in Turkey equipped with little but a beat-up edition of Homer's "Iliad." Schliemann was determined to discover ancient Troy - and so he did.

For the longest time, the German public used to make light of Schliemann's achievements, as his biggest rival, top archeological expert Ernst Curtius, repeatedly mocked him in a bid to polish his own professional profile. Schliemann was, however, much more appreciated in Britain, where the German researcher has always been celebrated as the man who discovered the ancient city of Troy - a place, which up to that point had been shrouded in mystery.

Schliemann went on to invent research methods in the late 19th century, which are still in use today. His story is one which shaped the face of archeology unlike any other.

A business man and adventurer

From his early childhood onwards, the ancient world had always fascinated Schliemann. Yet his career path had initially pointed in a different direction. Raised alongside eight other siblings in a pastor's family in the eastern part of the Mecklenburg province, Schliemann started out as a tradesman, as his family could not afford to send him to higher education.

He ended up in Amsterdam, where within one year, he learned to speak not only Dutch, but also Spanish, Italian and Portuguese, to be complemented by Russian later on. His extraordinary gift for foreign languages paved the way for a different career prospect: archeology.

After then moving to Russia, Schliemann became rich dealing with raw materials for the production of ammunition. He used his fortune to study Ancient Greek and Latin in Paris.

In 1868, he went on an educational trip to the Greek island of Ithaka, where he decided to look for the palace of Ulysses. From there, he traveled to the Marmaris Sea to make his way inland and start the quest for Troy. During his entire journey, Homer's "Iliad" was Schliemann's one and only true companion, the one book he considered his indispensable guide to discover Troy.

Following Homer's footsteps

The search for the ancient city of Troy had never ceased for over thousands of years. But in all that time, no one had ever been able to prove that Homer's saga of the Trojan War had actually occured - until 1871, when Heinrich Schliemann, then 49-years-old, discovered the ruins of the city under the Hisarlik hill in the Troas region in the northwest of present-day Turkey. Schliemann had by no means been the first person to believe that the city described by Homer was hidden under this particular location.

Before Schliemann, British archeologist Frank Calvert had already begun excavations in the very same region. The two Troy-obsessed researchers ran into each other by sheer coincidence. Calvert had actually acquired the land around Hisarlik so he could continue with his work, but he lacked the funds to continue with his excavation attempts, which, at that point, had run into a dead end.

Calvert persuaded Schliemann to continue where he had stopped working. After running into a number of initial impasses, Heinrich Schliemann stubbornly continued with the excavations until in 1872 he hit meter-high ruins of belonging to a prehistoric city. Schliemann came to the conclusion that these walls had once formed part of the fortification of Troy.

It had been a difficult journey for both men, as the precise identification of the findings was rendered all the more difficult due to the long history of the city, which had first surfaced in records in 3000 BC.

Errors in classification

Among his most significant discoveries in Troy, Heinrich Schliemann struck a cache of gold and other artifacts, which he subsequently baptized "the treasure of Priam" in 1873. He smuggled the gold treasure out of the country and gave it to the German government to showcase. But the treasure got lost in the throes of World War II, only to later resurface in Russia, where it is now being kept at the Pushkin Museum.

It later turned out that Schliemann's claim to the treasure had been wrong all along. His findings did not amount to the treasure of Priam, but were rather a relic from an unknown culture, which had flourished 1250 years before ancient Troy.

This wasn't the only time that the German explorer had erred. At the Greek archeological site of Mycenae, where Schliemann carried out excavations from 1874 to 1876, he drew a number of wrong conclusions based on his work. Schliemann wrongfully identified a golden mask as having belonged to the ancient Greek military leader Agamemnon.

Despite his errors and wrong conclusions, the world continued to venerate Heinrich Heinrich Schliemann as one of the most significant archeologists of all times.

He died in Naples on December 6, 1890.

Fonte: Deutsche Welle

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário