Prostitution, they claim, is the oldest profession in the world, but when it comes to Ottoman times very little is known - not just because little research has been done on it. While marriage, divorce, slavery and adultery are extensively regulated in Ottoman customary law and Muslim law, the sharia, prostitution is not. Moreover, researchers are inclined to complain that cases cited in Ottoman records are often not specific enough to determine whether a complaint of “immorality” actually involves prostitution.

One of the first times we hear about prostitutes is in the last years of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent reign (r. 1522-1566). The incident occurred one day in 1565, according to Refik Ahmet Sevengil’s “Istanbul Nasıl Eğleniyordu.” The locals in a district called Sultangir got together and went to the local kadı (judge) and complained about five women who were residents of the area. The five women whose names were Arap Fati, Narin, Giritli Nefise, Kamer -who was also known as Atlı Ases - and Balatlı Yumni. The complaint was that these women were openly engaged in prostitution. Of the five women, only Arap Fati refused to appear before the judge when summoned. It was decided that the houses of these women would be sold and the women expelled from the city.

When the imam (prayer leader) came to Arap Fati’s house, she cursed the imam, the kadı and sharia law and it was determined that she had let strangers (men who were not her father, husband or brother) into her house. Her anger arose over the fact that she had had the same situation occur to her in a different area of Istanbul and, as her husband was a Janissary and therefore out on one of the many military campaigns, she had turned to prostitution to survive. Needless to say, her house was sold and she was remanded to prison until her husband returned.

Crime and punishment

Prostitution wasn’t confined to one place at this time, but could be seen throughout Istanbul. Just two years after the anecdote cited above, Sultan Selim II (r. 1566 -1574) issued a decree calling for an investigation into prostitution and immorality in the city and the registration of all concerned and their punishment; prostitutes were to be imprisoned. Obviously, the call to stamp out prostitution was not very successful because it was too easy to bribe the related officials into looking the other way.Marinos Sariyannis in “Prostitution in Ottoman Istanbul, Late Sixteenth – Early Eighteenth Century” comments that the law seems to have been rather vague leading many jurists in the 16th century to consider prostitution legal but pandering was a crime. The Ottomans preferred to exact fines from the women who were performing a kind of “adultery” and this seems to have suited the prostitutes as well because they had no hesitation in going to the kadı to demand that she be paid for her services. The author also cites the instance of the governor of Damascus in the 18th century who gave up on decrees and punishments and instead demanded a monthly payment from each prostitute. In 1703, Edirne was apparently filled with “adulterous women and the basest of men” and once again officials were commanded to go from neighborhood to neighborhood registering everybody.

In the 19th century, meyhanes (taverns) opened in many places throughout Istanbul, from Yenikapı to Hasköy and from Beyoğlu/Galata to Kadıköy. Usually the servants in these places were beautiful young boys, although the entertainment might be provided by women dancing and singing. By this time trafficking in women from the Balkans was well established in Istanbul, with gangs recruiting and circulating women through a number of destinations such as Izmir and Trieste. Foreigners were granted permission to work out of whore houses in certain areas while Muslim women were technically forbidden from engaging in prostitution. However, the latter were known to be operating in houses in Muslim districts such as Aksaray with the full knowledge of neighbors.

Various consulates took an interest in “rescuing” any woman who was underage if her family requested their aid. The consulate most frequently engaged in this activity was that of Austria. The Turkish police tended to not interfere in what was happening to foreigners and this message soon got through to the various traffickers who then acquired Turkish citizenship so that they would have the protection of Turkish law vis-à-vis the foreign consulates.

Young boys and prostitution

While westerners tend to think of prostitutes as female, Ottoman culture was such that a great deal of emphasis was placed on the beauty of young boys. Walter G. Andrews and Mehmet Kalpaklı reflect on this situation in their book, “The Age of Beloveds”: “In situations where public life is dominated by men [as it was among the Ottomans], where warfare is frequent and many men spend most of their time as warriors in the company of other men, and where men are educated and women are not, what people identified as masculine virtues – for example, strength, bravery, physical prowess, male beauty, artistic talent, eloquence – are highly valued. Being attracted to young men, loving young men, is an affirmation of those values and virtues, the very values and virtues that a man seeks in himself. One may also be attracted to women and enjoy relations with them, but the relationship must always be hugely unequal in regard both to distributions of power and to the sharing of cultural expectations.”In Ottoman society, women in the more affluent classes were confined to their homes except for those among the poor who had perforce to go outside to shop and obtain necessities for their families. So it is not surprising to find young boys/men in a variety of roles such as bath attendants or waiters in taverns. It did not take long for the owners to catch on that if the boys were attractive then more men were likely to frequent their establishments. Andrews and Kalpaklı cite the case of the poet Gazali who built a mosque complex in Beşiktaş and staffed it with beautiful young men. It proved to be so popular that other bathhouse owners lodged complaints against him and eventually it was torn down. The authorities it seems turned a blind eye to the practice and to the availability of these young boys, but only until it resulted in social outrage or rape. Punishment was not consistent and was administered on an ad hoc manner depending on the situation.

Fonte: Hurriyet Daily News

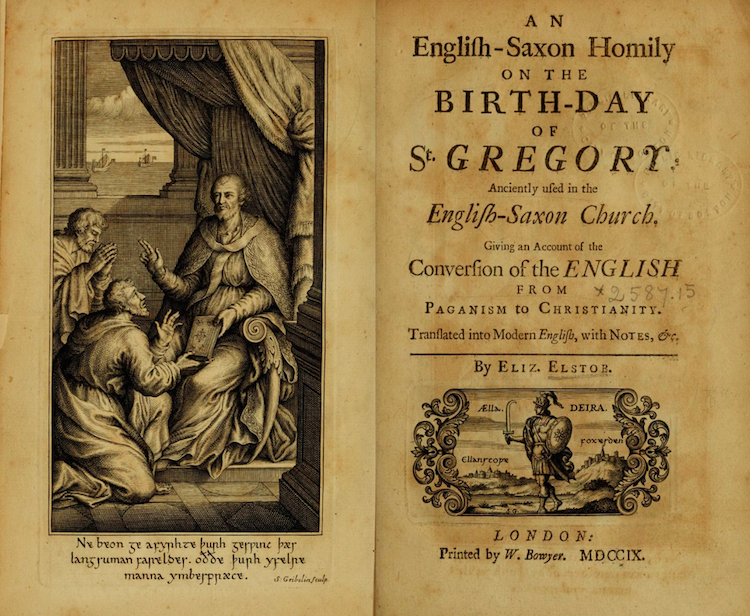

Frontispiece for Elstob's An Anglo-Saxon Homily on the Birthday of Saint Gregory (1709).

Frontispiece for Elstob's An Anglo-Saxon Homily on the Birthday of Saint Gregory (1709).